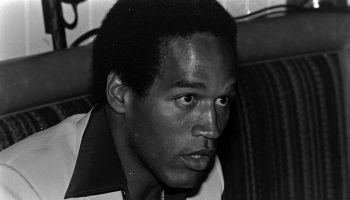

Remembering Malcolm’s Murder, 45 Years Later

Date: Monday, February 22, 2010, 6:46 am

By: Deborah Mathis, BlackAmericaWeb.com

In February 1965, there was no Black History Month – only Negro History Week, the second week of the second month, thereby predating what would later become the bitter irony of Malcolm X’s assassination in February, of all months.

I was not quite 12 years old when three men stepped out of the crowd at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem on February 21 and shot the man at center stage 16 times, beginning with a sawed-off shotgun blast to the chest. Even in the risky, unraveling 1960s – even after the innocence-shattering horror of JFK’s assassination – the murder of Malcolm X was an unspeakable act of terror.

The black community was stunned and hurt. Malcolm had not been everyone’s cup of tea, not by a long shot. At a time when many black folks found the peace-loving Martin Luther King, Jr. too radical for their taste, Malcolm was a hell-raising, troublemaker who only inspired white folks to a greater meanness and, therefore, someone they wished would go away. But not like this. Even the cowed were infuriated by the atrocity in Harlem that late winter day.

The day after Malcolm was slain, the New York Times – then, like now, considered not only the newspaper of record but an enlightened one – published a troublesome editorial.

“Malcolm X had the ingredients for leadership,” the Times opined, “but his ruthless and fanatical belief in violence not only set him apart from the responsible leaders of the civil rights movement and the overwhelming majority of Negroes. It also marked him for notoriety, and for a violent end.”

In short, he asked for it.

Certainly, fairer writers would have remembered Malcolm for more than his fiery, militant rhetoric, dripping with sarcasm, ridicule, rebellion and menace. Indeed, Malcolm had been worrisome – a thief and drug dealer and pimp, then a religious fanatic, revolutionary and insurrectionist.

But, in the end, Malcolm was reformed, some would say, reinvented yet again. His conversion was not nuanced. Starkly, nakedly, plainly, he denounced his prior racism and struck a conciliatory chord. To this day, many believe his break from Elijah Muhammad’s cultish and bizarre brand of Islam – and his ability to sway so many followers – is what got him killed. A fact-checker might have been helpful to the Times editorialist.

In truth, even when Malcolm was at the height of his hell-raising, he deserved more respect than the establishment would have ever afforded him.

Although his tactics and aims were different from his contemporary, Dr. King, the brilliant, disarming, charismatic Malcolm X realized that the polarization could be productive.

“I want Dr. King to know that I didn’t come to Selma to make his job difficult,” he said on a trip to the Alabama cauldron. “I really did come thinking I could make it easier. If the white people realize what the alternative is, perhaps they will be more willing to hear Dr. King.”

It’s been 45 years since that awful day when Betty Shabazz watched her husband collapse from mortal wounds while the couple’s young daughters looked on. Dr. King is long gone. Sister Betty is gone. So too is Alex Haley, who so perfectly captured his subject in “The Autobiography of Malcolm X.” Elijah Muhammad is gone. The fabulous actor and activist Ossie Davis, who eulogized Malcolm as “our bright, shining prince,” is no more. And the three men convicted of the assassination have served their time and long since been paroled.

Two new generations have come of age since Malcolm’s death, and many know of him only from posters or t-shirts or black caps with a white “X” or infamous quotes or Spike Lee’s biopic.

Whether knowing Malcolm is from word of mouth or from precious memory, it is clear that the Times couldn’t have been more wrong when it wrote that the leader’s life was “strangely and pitifully wasted.”